By Nicholas B. Dirks

My journey leading the New York Academy of Sciences roughly coincides with the global calamity of SARS-CoV-2. As I reflect on my two-year anniversary, I cannot help but consider how much we have depended on scientists for the development of vaccines and therapeutics. Even though we are still experiencing the long tail of the pandemic, we are beginning to feel the worst may be behind us. One consequence is that we can more fully turn our attention to other crises, especially the very real dangers of climate change.

The global response to the COVID-19 pandemic was remarkable, but there were shortfalls, too. One lesson was the importance of preparation, and it is to improve scientific preparation for the next global crisis—no matter what it might be—that we are making great strides with the International Science Reserve. It’s an ambitious program to pre-position resources that scientists will need—and to ready scientists themselves—to conduct research and find evidence-based solutions to global emergencies.

That’s a big part of our mission, along with improving science literacy, promoting interdisciplinary and innovative science, and supporting the training of new generations of scientists. While the Academy is 200 years old, as we head toward the mid-21st century we are fulfilling our mission in new, forward-looking ways. Let me provide some updates, and ask for your continued support for our critically-important work.

The International Science Reserve

We have just completed our first readiness exercise for the International Science Reserve (ISR). Scientists in our ISR Member Network—which stands a thousand strong, with representation from 90 countries—submitted research proposals in response to simulated wildfire emergencies in the U.S., Greece, and Indonesia. We are analyzing the proposals to learn:

- What data, data-gathering resources, equipment, facilities, and personnel are needed to support scientists in crisis response;

- What resources transcend specific types of crises and thus can be put in place now;

- What systems for resource matching and the mobilization of scientists should be in place for quick responses to global emergencies.

Early-Career Science

We are working on the ISR with IBM, UL, Google, Pfizer and other partners. But we need your support to run additional readiness exercises, and to use our findings in building an operations plan. The goal is nothing less than to maximize the power of science to save lives, livelihoods, and the environment.

The Academy is helping young scientists at the most critical stage of their careers, as they transition from graduate school toward success in professional research.

K-12 STEM

The Academy works with younger scientists too. We nurture early interest in science among ever more diverse groups of young people. With the support of EnCorps, for example, we’re placing scientists in in classrooms across New York City’s five boroughs. In a partnership with the Clifford Chance law firm and Ericcson, we’ve enrolled more than 500 students in Rwanda and Oman in STEM innovation challenges. We are working to diversify and expand STEM education in scores of countries around the world, including with a new program in Colombia.

Mentorship

We are helping scientists give back, across all levels of education. Our Mentors Program places experienced scientists with young people in classrooms and alongside student teams working on extracurricular projects. Our mentors also advise older students as they enter the workforce and our programs support scientists who may wish to change careers, to work as teachers themselves.

- With this letter, I am announcing our partnership with the Leon Levy Foundation to support neuroscience post docs at universities and medical centers across the New York metropolitan area. The plan is to help remove barriers to advancement and provide significant support for the best and brightest young minds in the field.

- Our Science Alliance brings graduate students and post docs together to gain communications and management skills, and to learn about professional opportunities and career strategies, including ways to fight bias in the workplace.

- To support our belief that the best science takes place when problems are attacked with interdisciplinary perspectives by people from diverse backgrounds, we run the Interstellar Initiative with the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. It is a 6-month workshop to support teams of young scientists from around the world in developing innovative research proposals in the life sciences.

- Our awards programs focus on early career scientists, to help them advance to become leaders in their fields.

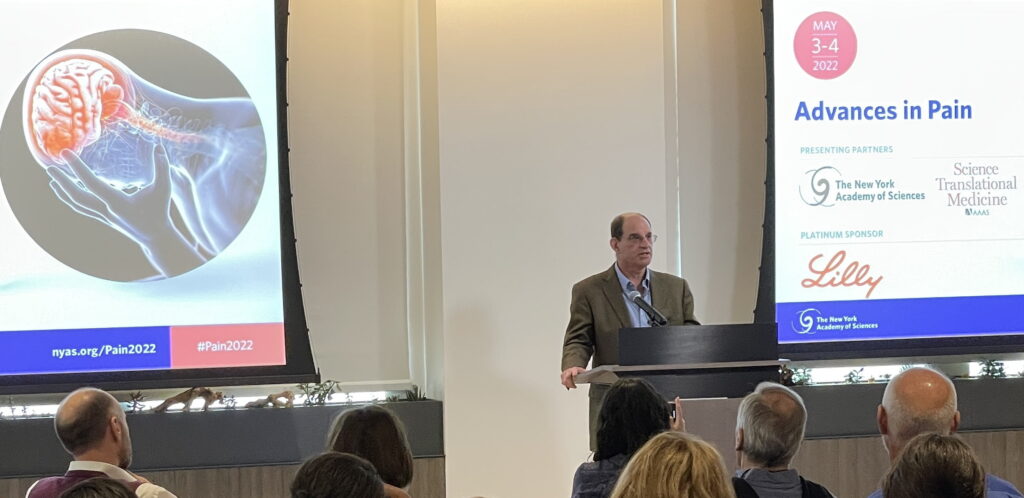

Scientific Convenings

Of course, we continue to convene scientists and policy experts for the exchange of scientific knowledge. Each year, our conferences feature Nobel Prize laureates and dozens of other researchers at the leading edge of their fields. We help specialists work together, and we tackle topics that grab the attention of broader audiences. Examples include a series on new evidence for the therapeutic value of psychedelics, ways to recognize and reduce bias in the health sciences, and continuing reports on SARS-CoV-2.

Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences

Our multidisciplinary science journal, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, publishes research of current interest for the broad scientific community and society at large. Recent articles have presented work on mathematics anxiety and performance, the benefits of micronutrients during pregnancy, and the biodiversity and composition of bat communities.

We are an independent, democratic organization, open to all who want to help advance science. Now, more than ever, we believe that this commitment is critically important for the lives of our children and grandchildren. Geopolitical forces continue to drive us apart in ways that not only fracture the world but also the practice and advancement of science. We work to bridge those divides, and to foster collaboration, innovation, and the imagination we need to solve our global challenges.

We receive no government funding, and your support plays a critical role in helping science—and scientists—work toward a better, safe, and prosperous world. Please continue your valuable support for the New York Academy of Sciences.