Following the release of the 2016 WHO Guidelines for Antenatal Care, The New York Academy of Sciences assembled a scientific task force comprised of international experts in micronutrient deficiencies, public health, nutrition, pediatrics and health economics to:

- Compile the evidence on the prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies in pregnant women or women of reproductive age

- Review the evidence on the benefits and risks of multiple micronutrient supplements on maternal and perinatal outcomes

- Create a roadmap to guide decisions in countries considering the implementation of such programs.

The findings from the first phase of this initiative show that substantial benefits may be expected, in terms of mortality reduction and poor birth outcome, by shifting from IFA to MMS in Antenatal Care programs.

Promoting MMS in Low and Middle-Income Countries

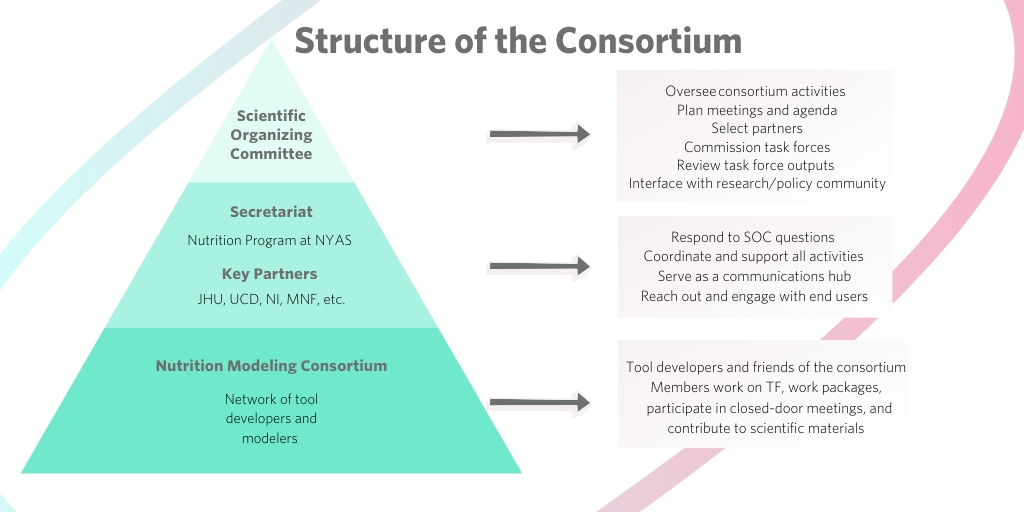

The Multiple Micronutrient Supplementation Technical Advisory Group (TAG) assists countries considering the use of multiple micronutrient supplements in their antenatal care programs. The New York Academy of Sciences and the TAG have collaborated with UNICEF, with funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, to promote the uptake of MMS by pregnant women in a number of pilot low and middle-income countries (LMICs). These promotional efforts encompass the following activities:

- Recruitment and coordination of a Technical Advisory Group (TAG) to provide evidence and materials to governments in LMICs so that they can tailor the use of MMS to their specific conditions

- Facilitation of global MMS efforts, via the creation of a communications hub to advise and document the pilot phase throughout the planned implementation

- Provision of technical support to UNICEF as it rolls out MMS in four pilot countries (Bangladesh, Madagascar, Burkina Faso and Tanzania), as well as other locations considering making the switch from iron and folic acid to MMS

For this initiative, UNICEF assisted with the rollout and implementation of MMS in pilot LMIC countries. Vitamin Angels supplied the product and provision of MMS. The Healthy Mother’s Healthy Babies Consortium brought together stakeholders, including country representatives, research and knowledge institutions, non-governmental organization (NGOs), technical organizations, UN agencies, private sector stakeholders, and funders to work together to raise awareness, trigger policy change and accelerate adoption of MMS.

Review of Evidence

Why MMS?

Multiple-micronutrient deficiencies often coexist among women of reproductive age (WRA) in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). This may put their health and that of their offspring at risk, especially during pregnancy when micronutrients requirements increase. Multiple micronutrient supplements (MMS) may fill those gaps but in 2016 the WHO Guidelines for Antenatal Care reaffirmed their recommendation of IFA for routine use in pregnancy. WHO’s recommendation was based on “…some evidence of risk, and some important gaps in the evidence”. The WHO Guideline however, commented that “policy-makers in populations with a high prevalence of nutritional deficiencies might consider the benefits of MMS on maternal health to outweigh the disadvantages, and may choose to give MMS”.

Since the release of the 2016 ANC Guidelines, two important reviews were carried out that provided high quality evidence on the potential benefits to be gained in terms of various antenatal and maternal outcomes by switching from IFA to MMS. Specifically, the IDP meta-analysis found that, when compared to IFA alone, MMS would:

- Reduce the risk of stillbirth

- by 8% in the overall population of pregnant women

- by 21% in the group of anemic pregnant women

- Reduce the risk of mortality among 6-month infants

- by 29% in the group of anemic pregnant women

- by 15% in female infants

- Reduce the risk of low birth weight (<2500g)

- by 12% in the overall population of pregnant women

- by 19% in the group of anemic pregnant women

- Reduce the risk of preterm (<37 weeks) birth

- by 8% in the overall population of pregnant women

- by 16% in the group of underweight women

- Reduce the risk of being born small-for-gestational age

- by 3% in the overall population of pregnant women

- by 8% in the group of anemic pregnant women

In 2020, WHO reviewed the new evidence that became available since the publication of the 2016 ANC Guidelines and updated the recommendations for MMS during pregnancy. These updated Guidelines now state that antenatal MMS that include IFA are recommended in the context of rigorous research.

Reference: Smith ER, Shankar AH, Wu LS-F, et al. Modifiers of the effect of maternal multiple micronutrient supplementation on stillbirth, birth outcomes, and infant mortality: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from 17 randomized trials in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob Heal. 2017;5(11):e1090-e1100.

MMS and COVID-19

- Preventing and controlling micronutrient deficiencies in populations affected by an emergency

- Use of MMS for maternal nutrition and birth outcomes during COVID

- Protecting Maternal Diets and Nutrition Services in the Context of COVID-19

Key Scientific Papers

- 2016 WHO Guidelines for Antenatal Care

- 2020 update on MMS – WHO Guidelines for Antenatal Care

- WHO recommendations on antenatal nutrition: an update on multiple micronutrient supplements

- 2019 Cochrane Review

- 2017 Lancet GH Review

- Review of the evidence regarding the use of MMS in low‐ and middle‐income countries

- Replacing IFA with MMS among pregnant women in Bangladesh and Burkina Faso: costs, impacts, and cost‐effectiveness

- The upper level: examining the risk of excess micronutrient intake in pregnancy from antenatal supplements

- Benefits of MMS supplementation in pregnancy

- Expert consensus on an open-access UNIMMAP–MMS product specification

- Setting research priorities on multiple micronutrient supplementation in pregnancy

- Interventions to increase adherence to micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy: a protocol for a systematic review

- Antenatal multiple micronutrient supplementation: call to action for change in recommendation (letter to the editor)

- Multiple micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy: a decade of collaboration in action

- Interventions to Increase Adherence to Micronutrient Supplementation During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review

- Multiple micronutrient supplements versus iron-folic acid supplements and maternal anemia outcomes: an iron dose analysis

- Effect of multiple micronutrient supplements v. iron and folic acid supplements on neonatal mortality: a reanalysis by iron dose

- Micronutrient supplements in pregnancy: an urgent priority

- Antenatal multiple micronutrient supplements versus iron-folic acid supplements and birth outcomes: Analysis by gestational age assessment method

Reports

- Meeting 1 Report

- Meeting 2 Report

- eBriefing: Improving Birth Outcomes with Multiple Micronutrient Supplementation

- MMS Implementation Meeting Report

- Decision-maker Guidance

- Decision-maker Guidance (French)

- Decision-maker Guidance (Spanish)

- MMS Iron Dose Summary

Technical Reference Materials

- TRM I: Technical Brief for Policy Makers

- TRM II: Training Materials

- TRM III: Logistics of Implementation

- FAQ

Background Materials

Torheim, L.E., Ferguson, E.L., Penrose, K., Arimond, M. (2010). Women in Resource-Poor Settings Are at Risk of Inadequate Intakes of Multiple Micronutrients. J Nutr, 140(11): 2051S-2058S

Pathak, P., Kapil, U., Yajnik, C. S, Kapoor, S. K., Dwivedi, S. N., & Singh, R. (2007). Iron, Folate, and Vitamin B12 Stores among Pregnant Women in a Rural Area of Haryana State, India. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 28(4): 435–438.

Lee, S., Talegawkar, S., Merialdi, M., & Caulfield, L. (2013). Dietary intakes of women during pregnancy in low- and middle-income countries. Public Health Nutrition, 16(8): 1340-1353.

Kulkarni, B., Christian, P., LeClerq, S., & Khatry, S. (2010). Determinants of compliance to antenatal micronutrient supplementation and women’s perceptions of supplement use in rural Nepal. Public Health Nutrition, 13(1), 82-90.

Gernand, A. D., Schulze, K. J., Stewart, C. P., West, K. P., & Christian, P. (2016). Micronutrient deficiencies in pregnancy worldwide: health effects and prevention. Nature reviews. Endocrinology, 12(5), 274-89.

Lu, C., Black, M. M., & Richter, L. M. (2016). Risk of poor development in young children in low-income and middle-income countries: an estimation and analysis at the global, regional, and country level. The Lancet. Global health, 4(12), e916-e922.

Jiang, T., Christian, P., Khatry, S.K., Wu, L., West, K.P. (2005). Micronutrient Deficiencies in Early Pregnancy Are Common, Concurrent, and Vary by Season among Rural Nepali Pregnant Women. J Nutr, 135(5), 1106-1112.

Project Outcomes

This initiative, supported by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, is a collaboration between UNICEF, the MMS Technical Advisory Group, and the New York Academy of Sciences. Activities carried out through this effort include:

- The development of a Communications Hub to link the various stakeholders (scientists, implementers, multilateral organizations, policy makers and the private sector) involved in MMS programs

- The coordination of technical support to adopting countries, including the preparation of technical reference materials to explain and organize MMS programs and to train the health workforce in their implementation

- UNICEF implementation of a MMS rollout in 4 pilot countries (Bangladesh, Madagascar, Burkina Faso and Tanzania)

- Promote and support MMS programs in additional countries as needed

- A webinar to disseminate the findings of the scientific task force

- A systematic review on interventions to increase adherence to micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy

MMS Meeting Workshops

Core Product Specification Workshop, November 11-12, 2019

On November 11th and 12th, 2019, the Academy and the Micronutrient Forum (MNF) co-hosted a workshop in Washington DC to develop a Core Product Specification for multiple micronutrient supplement in pregnancy.

Task Force on Multiple Micronutrient Supplementation (MMNS) in Pregnancy, April 17-18, 2018

Second of two closed door technical consultation at the Academy. While the first meeting examined the benefits and potential risks of multiple micronutrient supplementation, the second consultation focused primarily on considerations for the development of a roadmap to guide countries considering multiple micronutrient supplement implementation

Task Force on Multiple Micronutrient Supplementation in Pregnancy, November 15-16, 2017

First of two closed-door technical consultations at the Academy to review recent evidence on the benefits and risks of multiple micronutrient supplementation, identify research gaps, and determine which populations may benefit most from supplementation.

Contact Us

To learn more about our MMS Initiative, contact us at nutrition@nyas.org.

Funding Support

Organized By