From the future of higher education to regulating artificial intelligence (AI), Reid Hoffman and Nicholas Dirks had a wide-ranging discussion during the first installment of the Authors at the Academy series.

Published April 12, 2024

By Nick Fetty

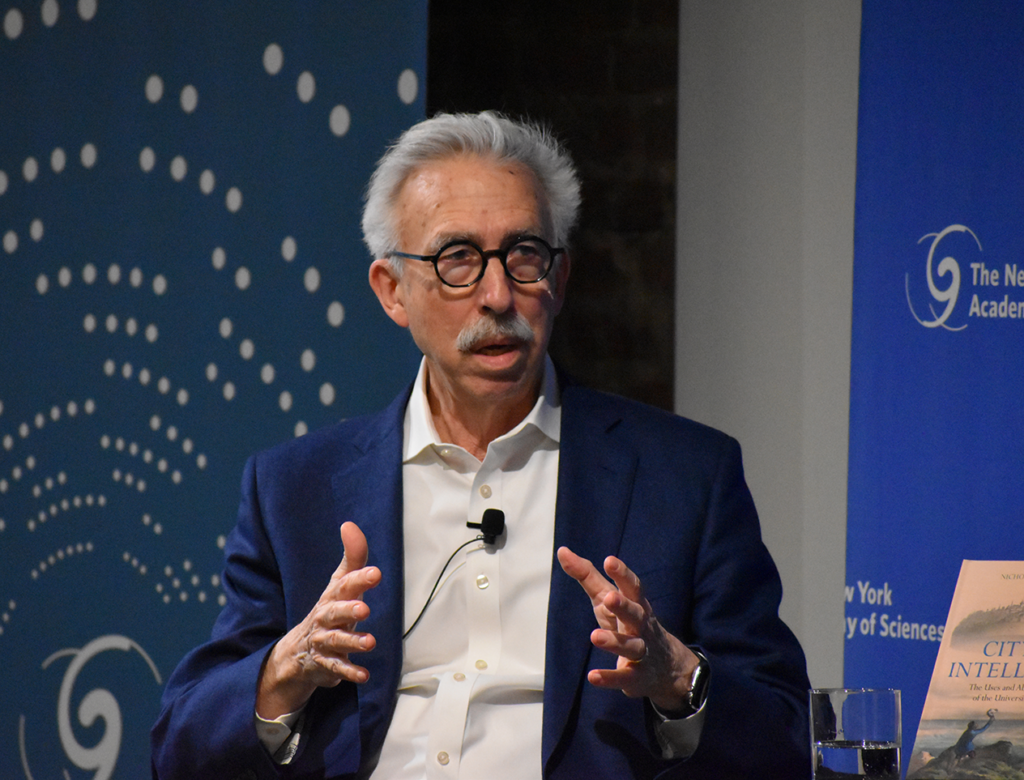

It was nearly a full house when authors Nicholas Dirks and Reid Hoffman discussed their respective books during an event at The New York Academy of Sciences on March 27, 2024.

Hoffman, who co-founded LinkedIn as well as Inflection AI and currently serves as a partner at Greylock, discussed his book Impromptu: Amplifying Our Humanity Through AI. Dirks, who spent a career in academia before becoming President and CEO of the Academy, focused on his recently published book City of Intellect: The Uses and Abuses of the University. Their discussion, the first installment in the Authors at the Academy series, was largely centered on artificial intelligence (AI) and how it will impact education, business and creativity moving forward.

The Role of Philosophy

The talk kicked off with the duo joking about the century-old rivalry between the University of California-Berkeley, where Dirks serves on the faculty and formerly served as chancellor, and Stanford University, where Hoffman earned his undergraduate degree in symbolic systems and currently serves on the board for the university’s Institute for Human-Centered AI. From Stanford, Hoffman went to Oxford University as a Marshall Scholar to study philosophy. He began by discussing the role that his background in philosophy has played throughout his career.

“One of my conclusions about artificial intelligence back in the day, which is by the way still true, is that we don’t really understand what thinking is,” said Hoffman, who also serves on the Board of Governors for the Academy. “I thought maybe philosophers understand what thinking is, they’ve been at it a little longer, so that’s part of the reason I went to Oxford to study philosophy. It was extremely helpful in sharpening my mind toolset.”

Public Intellectual Discourse

He encouraged entrepreneurs to think about the theory of human nature in the work they’re doing. He said it’s important to think about what they want for the future, how to get there, and then to articulate that with precision. Another advantage of a philosophical focus is that it can strengthen public intellectual discourse, both nationally and globally, according to Hoffman.

“It’s [focused on] who are we and who do we want to be as individuals and as a society,” said Hoffman.

Early in his career, Hoffman concluded that working as a software entrepreneur would be the most effective way he could contribute to the public intellectual conversation. He dedicated a chapter in his book to “Public Intellectuals” and said that the best way to elevate humanity is through enlightened discourse and education, which was the focus of a separate chapter in his book.

Rethinking Networks in Academia

The topic of education was an opportunity for Hoffman to turn the tables and ask Dirks about his book. Hoffman asked Dirks how institutions of higher education need to think about themselves as nodes of networks and how they might reinvent themselves to be less siloed.

Dirks mentioned how throughout his life he’s experienced various campus structures and cultures from private liberal arts institutions like Wesleyan University, where Dirks earned his undergraduate degree, and STEM-focused research universities like Cal Tech to private universities in urban centers (University of Chicago, Columbia University) and public, state universities (University of Michigan, University of California-Berkeley).

While on the faculty at Cal Tech, Dirks recalled he was encouraged to attend roundtables where faculty from different disciplines would come together to discuss their research. He remembered hearing from prominent academics such as Max Delbrück, Richard Feynman, and Murray Gell-Mann. Dirks, with a smile, pointed out the meeting location for these roundtables was featured in the 1984 film Beverly Hills Cop.

An Emphasis on Collaboration in Higher Education

Dirks said that he thinks the collaborative culture at Cal Tech enabled these academics to achieve a distinctive kind of greatness.

“I began to see this is kind of interesting. It’s very different from the way I’ve been trained, and indeed anyone who has been trained in a PhD program,” said Dirks, adding that he often thinks about a quote from a colleague at Columbia who said, “you’re trained to learn more and more about less and less.”

Dirks said that the problem with this model is that the incentive structures and networks of one’s life at the university are largely organized around disciplines and individual departments. As Dirks rose through the ranks from faculty to administration (both as a dean at Columbia and as chancellor at Berkeley), he began gaining a bigger picture view of the entire university and how all the individual units can fit together. Additionally, Dirks challenged academic institutions to work more collaboratively with the off-campus world.

“A Combination of Competition and Cooperation”

Dirks then asked Hoffman how networks operate within the context of artificial intelligence and Silicon Valley. Hoffman described the network within the Valley as “an intense learning machine.”

“It’s a combination of competition and cooperation that is kind of a fierce generator of not just companies and products, but ideas about how to do startups, ideas about how to scale them, ideas of which technology is going to make a difference, ideas about which things allow you to build a large-scale company, ideas about business models,” said Hoffman.

During a recent talk with business students at Columbia University, Hoffman said he was asked about the kinds of jobs the students should pursue upon graduation. His advice was that instead of pinpointing specific companies, jobseekers should choose “networks of vibrant industries.” Instead of striving for a specific job title, they should instead focus on finding a network that inspires ingenuity.

“Being a disciplinarian within a scholarly, or in some case scholastic, discipline is less important than [thinking about] which networks of tools and ideas are best for solving this particular problem and this particular thing in the world,” said Hoffman. “That’s the thing you should really be focused on.”

The Role of Language in Artificial Intelligence

Much of Hoffman’s book includes exchanges between him and ChatGPT-4, an example of a large language model (LLM). Dirks points out that Hoffman uses GPT-4 not just an example, but as an interlocutor throughout the book. By the end of the book, Dirks observed that the system had grown because of Hoffman’s inputs.

In the future, Hoffman said he sees LLMs being applied to a diverse array of industries. He used the example of the steel industry, in areas like sales, marketing, communications, financial analysis, and management.

“LLMs are going to have a transformative impact on steel manufacturing, and not necessarily because they’re going to invent new steel manufacturing processes, but [even then] that’s not beyond the pale. It’s still possible,” Hoffman said.

AI Understanding What Is Human

Hoffman said part of the reason he articulates the positives of AI is because he views the general discourse as so negative. One example of a positive application of AI would be having a medical assistant on smartphones and other devices, which can improve medical access in areas where it may be limited. He pointed out that AI can also be programmed as a tutor to teach “any subject to any age.”

“[AI] is the most creative thing we’ve done that also seems to have potential autonomy and agency and so forth, and that causes a bunch of very good philosophical questions, very good risk questions,” said Hoffman. “But part of the reason I articulate this so positively is because…[of] the possibility of making things enormously better for humanity.”

Hoffman compared the societal acceptance of AI to automobiles more than a century ago. At the outset, automobiles didn’t have many regulations, but as they grew in scale, laws around seatbelts, speed limits, and driver’s licenses were established. Similarly, he pointed to weavers who were initially wary of the loom before understanding its utility to their work and the resulting benefit to broader society.

“AI can be part of the solution,” said Hoffman. “What are the specific worries in navigation toward the good things and what are the ways that we can navigate that in good ways. That’s the right place for a critical dialogue to happen.”

Regulation of AI

Hoffman said because of the speedy rate of development of new AI technologies, it can make effective regulation difficult. He said it can be helpful to pinpoint the two or three most important risks to focus on during the navigation process, and if feasible to fix those issues down the road.

Carbon emissions from automobiles was an example Hoffman used, pointing out that emissions weren’t necessarily on the minds of engineers and scientists when the automobile was being developed, but once research started pointing to the detrimental environmental impacts of carbon in the atmosphere, governments and companies took action to regulate and reduce emissions.

“[While] technology can help to create a problem, technologies can also help solve those problems,” Hoffman said. “We won’t know they’re problems until we’re into them and obviously we adjust as we know them.”

Hoffman is currently working on another book about AI and was invited to return to the Academy to discuss it once published.

For on-demand video access to the full event, click here.

Register today if you’d like to attend these upcoming events in the Authors at the Academy series: