With a deep appreciation for the liberal arts, neuroscientist Marjorie Xie is developing AI systems to facilitate the treatment of mental health conditions and improve access to care.

Published May 8, 2024

By Nick Fetty

As the daughter of a telecommunications professional and a software engineer, it may come as no surprise that Marjorie Xie was destined to pursue a career in STEM. What was less predictable was her journey through the field of artificial intelligence because of her liberal arts background.

From the City of Light to the Emerald City

Marjorie Xie, a member of the inaugural cohort of the AI and Society Fellowship, a collaboration between The New York Academy of Sciences and Arizona State University’s School for the Future of Innovation in Society, was born in Paris, France. Her parents, who grew up in Beijing, China, came to the City of Light to pursue their graduate studies, and they instilled in their daughter an appreciation for STEM as well as a strong work ethic.

The family moved to Seattle, Washington in 1995 when her father took a job with Microsoft. He was among the team of software engineers who developed the Windows operating system and the Internet Explorer web browser. Growing up, her father encouraged her to understand how computers work and even to learn some basic coding.

“Perhaps from his perspective, these skills were just as important as knowing how to read,” said Xie. “He emphasized to me; you want to be in control of the technology instead of letting technology control you.”

Xie’s parents gifted her a set of DK Encyclopedias as a child, her first serious exposure to science, which inspired her to take “field trips” into her backyard to collect and analyze samples. While her parents instilled in her an appreciation for science and technology, Xie admits her STEM classes were difficult and she had to work hard to understand the complexities. She said she was easily intimated by math growing up, but certain teachers helped her reframe her purpose in the classroom.

“My linear algebra teacher in college was extremely skilled at communicating abstract concepts and created a supportive learning environment – being a math student was no longer about knowing all the answers and avoiding mistakes,” she said. “It was about learning a new language of thought and exploring meaningful ways to use it. With this new perspective, I felt empowered to raise my hand and ask basic questions.”

She also loved reading and excelled in courses like philosophy, literature, and history, which gave her a deep appreciation for the humanities and would lay the groundwork for her future course of studies. Xie designed her own major in computational neuroscience at Princeton University, with her studies bringing in elements of philosophy, literature, and history.

“Throughout college, the task of choosing a major created a lot of tension within me between STEM and the humanities,” said Xie. “Designing my own major was a way of resolving this tension within the constraints of the academic system in which I was operating.”

She then pursued her PhD in Neurobiology and Behavior at Columbia University, where she used AI tools to build interpretable models of neural systems in the brain.

A Deep Dive into the Science of Artificial and Biological Intelligence

Xie worked in Columbia’s Center for Theoretical Neuroscience where she studied alongside physicists and used AI to understand how nervous systems work. Much of her work is based on the research of the late neuroscientist David Marr who explained information-processing systems at three levels: computation (what the system does), algorithm (how it does it), and implementation (what substrates are used).

“We were essentially using AI tools – specifically neural networks – as a language for describing the cerebellum at all of Marr’s levels,” said Xie. “A lot of the work understanding how the cerebellar architecture works came down to understanding the mathematics of neural networks. An equally important part was ensuring that the components of the model be mapped onto biologically meaningful phenomena that could be measured in animal behavior experiments.”

Her dissertation focused on the cerebellum, the region of the brain used during motor control, coordination, and the processing of language and emotions. She said the neural architecture of the cerebellum is “evolutionarily conserved” meaning it can be observed across many species, yet scientists don’t know exactly what it does.

“The mathematically beautiful work from Marr-Albus in the 1970s played a big role in starting a whole movement of modeling brain systems with neural networks. We wanted to extend these theories to explain how cerebellum-like architecture could support a wide range of behaviors,” Xie said.

As a computational neuroscientist, Xie learned how to map ideas between the math world and the natural world. She attributes her PhD advisor, Ashok Litwin-Kumar, an assistant professor of neuroscience at Columbia University, for playing a critical role in her development of this skill.

“Even though my current research as a postdoc is less focused on the neural level, this skill is still my bread and butter. I am grateful for the countless hours Ashok spent with me at the whiteboard,” Xie said.

Joining a Community of Socially Responsible Researchers

After completing her PhD, Xie interned with Basis Research Institute, where she developed models of avian cognition and social behavior. It was here that her mentor, Emily Mackevicius, co-founder and director at Basis, encouraged her to apply to the AI and Society Fellowship.

The Fellowship has enabled Xie to continue growing professionally through opportunities such as collaborations with research labs, the winter academic sessions at Arizona State, the Academy’s weekly AI and Society seminars, and by working with a cohort of like-minded scholars across diverse backgrounds, including Tom Gilbert, PhD, an advisor for the AI and Society Fellowship, as well as the other two AI and Society Fellows Akuadasuo Ezenyilimba and Nitin Verma.

During the Fellowship, her interest in combining neuroscience and AI with mental health led her to develop research collaborations at Mt. Sinai Center for Computational Psychiatry. With the labs of Angela Radulescu and Xiaosi Gu, Xie is building computational models to understand causal relationships between attention and mood, with the goal of developing tools that will enable those with medical conditions like ADHD or bipolar disorder to better regulate their emotional states.

“The process of finding the right treatment can be a very trial-and-error based process,” said Xie. “When treatments work, we don’t necessarily know why they work. When they fail, we may not know why they fail. I’m interested in how AI, combined with a scientific understanding of the mind and brain, can facilitate the diagnosis and treatment process and respect its dynamic nature.”

Challenged to Look Beyond the Science

Xie says the Academy and Arizona State University communities have challenged her to venture beyond her role as a scientist and to think like a designer and as a public steward. This means thinking about AI from the perspective of stakeholders and engaging them in the decision-making process.

“Even the question of who are the stakeholders and what they care about requires careful investigation,” Xie said. “For whom am I building AI tools? What do these populations value and need? How can they be empowered and participate in decision-making effectively?”

More broadly, she considers what systems of accountability need to be in place to ensure that AI technology effectively serves the public. As a case study, Xie points to mainstream social media platforms that were designed to maximize user engagement, however the proxies they used for engagement have led to harmful effects such as addiction and increased polarization of beliefs.

She is also mindful that problems in mental health span multiple levels – biological, psychological, social, economic, and political.

“A big question on my mind is, what are the biggest public health needs around mental health and how can computational psychiatry and AI best support those needs?” Xie asked.

Xie hopes to explore these questions through avenues such as journalism and entrepreneurship. She wants to integrate various perspectives gained from lived experience.

“I want to see the world through the eyes of people experiencing mental health challenges and from providers of care. I want to be on the front lines of our mental health crises,” said Xie.

More than a Scientist

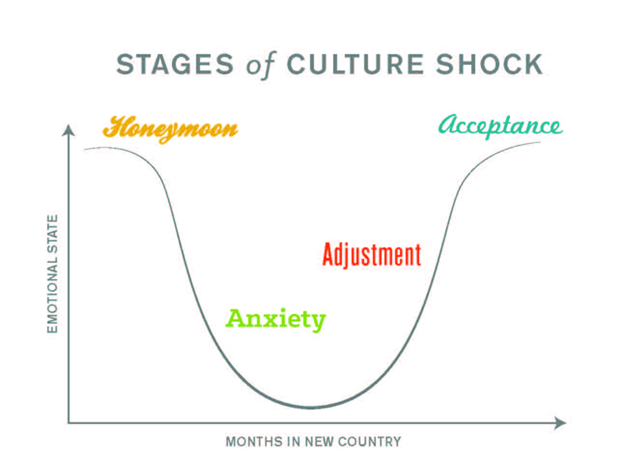

Outside of work, Xie serves as a resident fellow at the International House in New York City, where she organizes events to build community amongst a diverse group of graduate students from across the globe. Her curiosity about cultures around the world led her to visit a mosque for the first time, with Muslim residents from I-House, and to participate in Ramadan celebrations.

“That experience was deeply satisfying.” Xie said, “It compels me to get to know my neighbors even better.”

Xie starts her day by hitting the pool at 6:00 each morning with the U.S. Masters Swimming team at Columbia University. She approaches swimming differently now than when she was younger and competed competitively in an environment where she felt there was too much emphasis on living up to the expectations of others. Instead, she now looks at it as an opportunity to grow.

“Now, it’s about engaging in a continual process of learning,” she said. “Being around faster swimmers helps me learn through observation. It’s about being deliberate, exercising my autonomy to set my own goals instead of meeting other people’s expectations. It’s about giving my full attention to the present task, welcoming challenges, and approaching each challenge with openness and curiosity.”