By Douglas Braaten, PhD

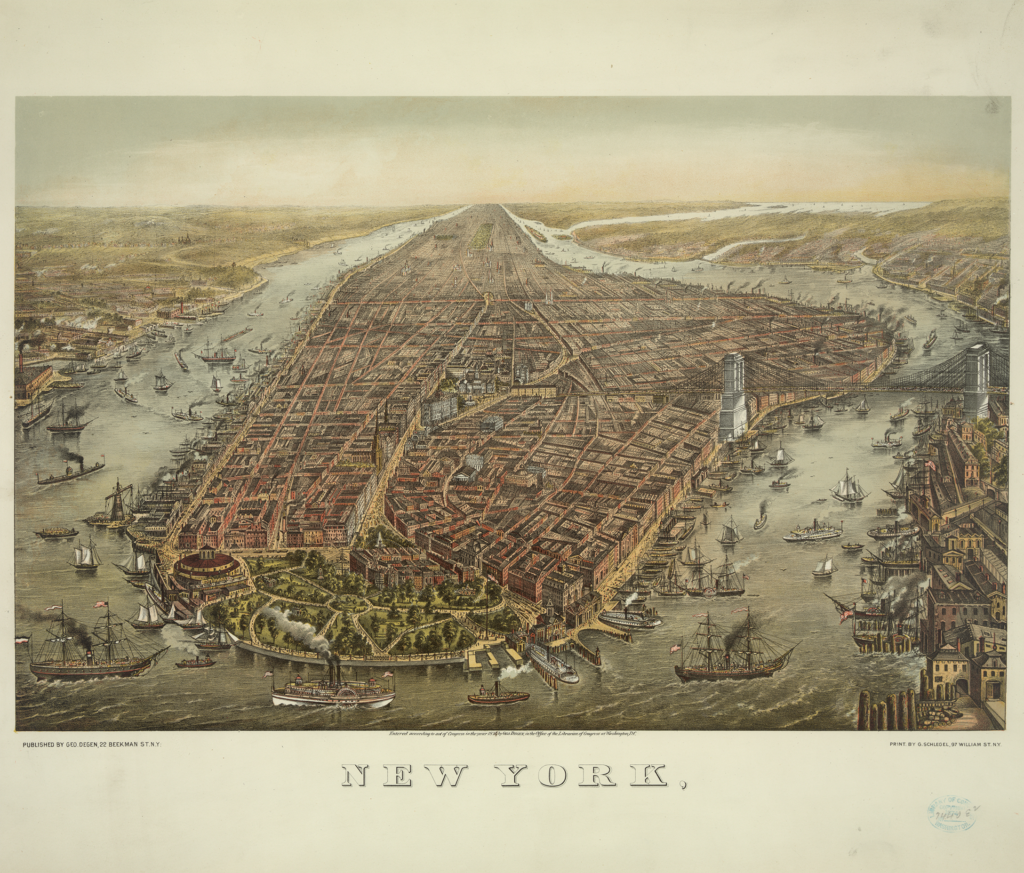

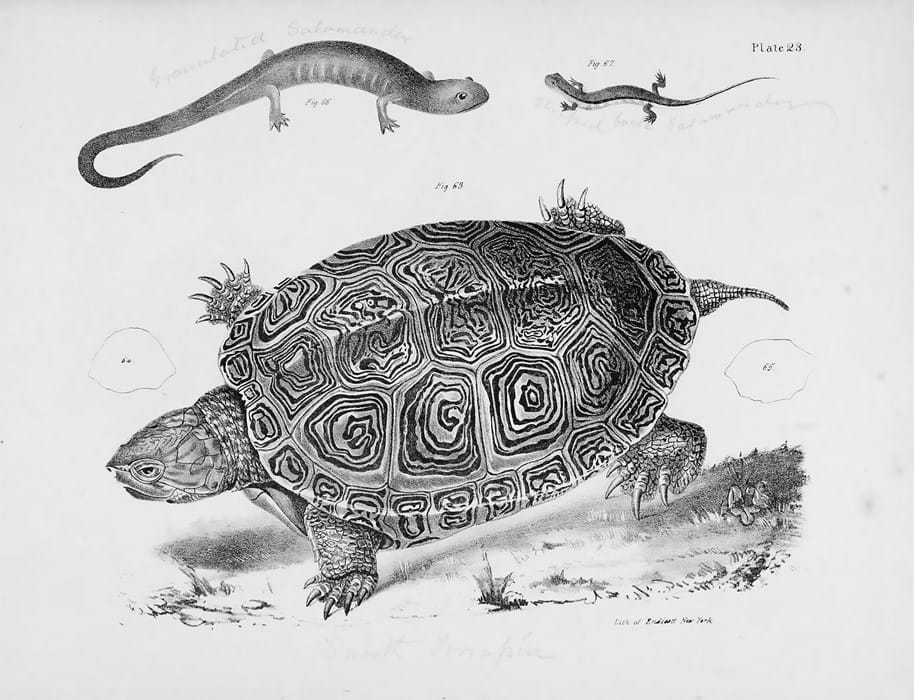

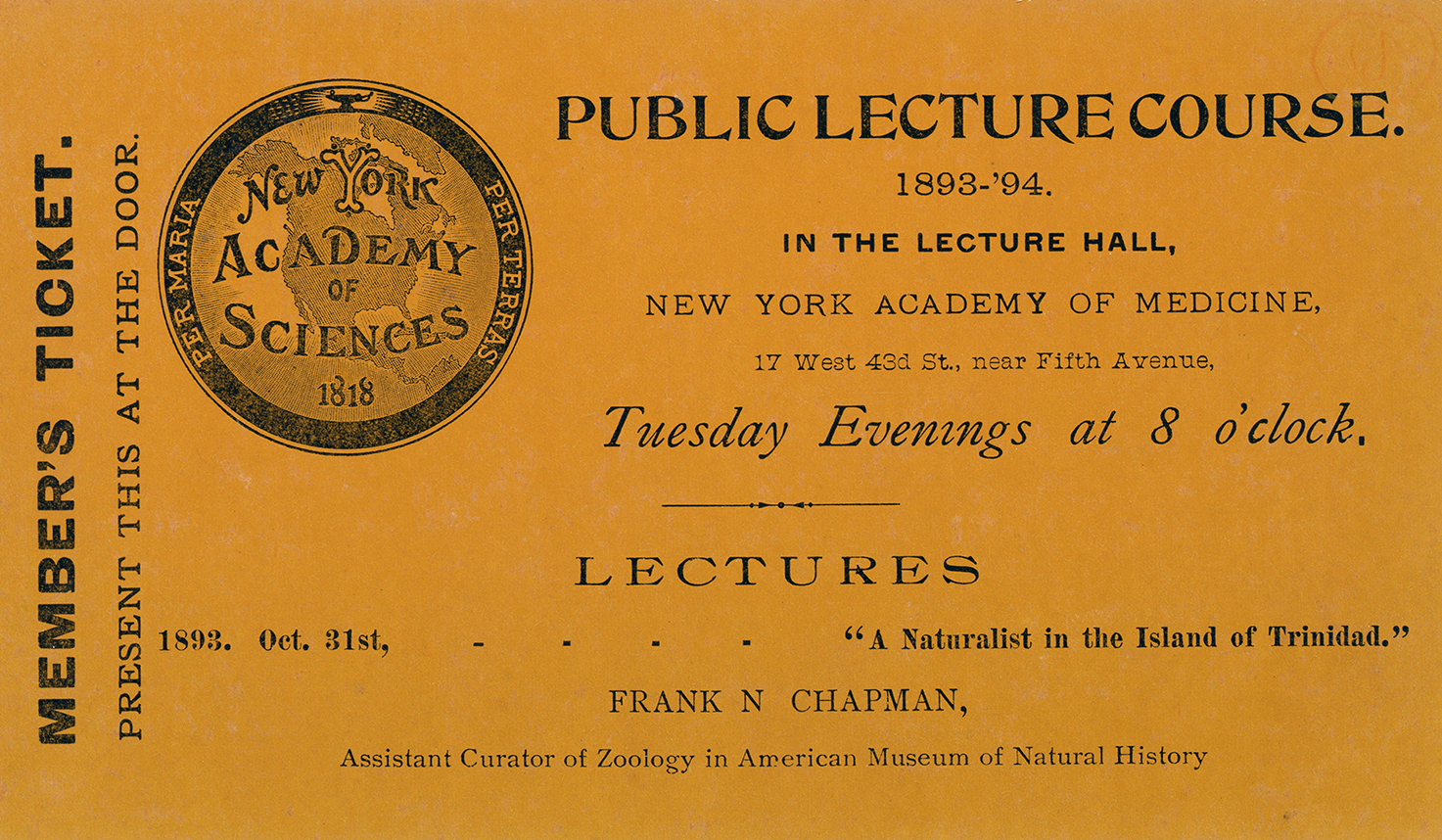

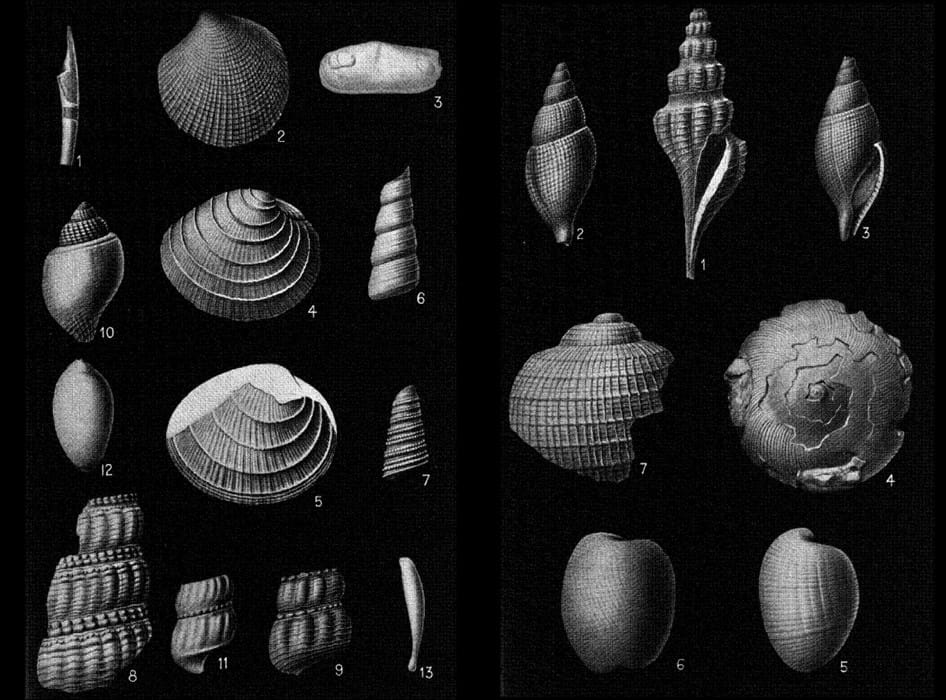

Founded in 1817 as the “Lyceum of Natural History in the City of New York,” by a small group of science enthusiasts, led by Samuel Latham Mitchill, a polymath and prominent politician who represented New York in the U.S. Congress, determined to create an organization that anyone interested in natural science could join in order to learn from experts, and that provided a venue for public consumption of scientific ideas and advances of the time.

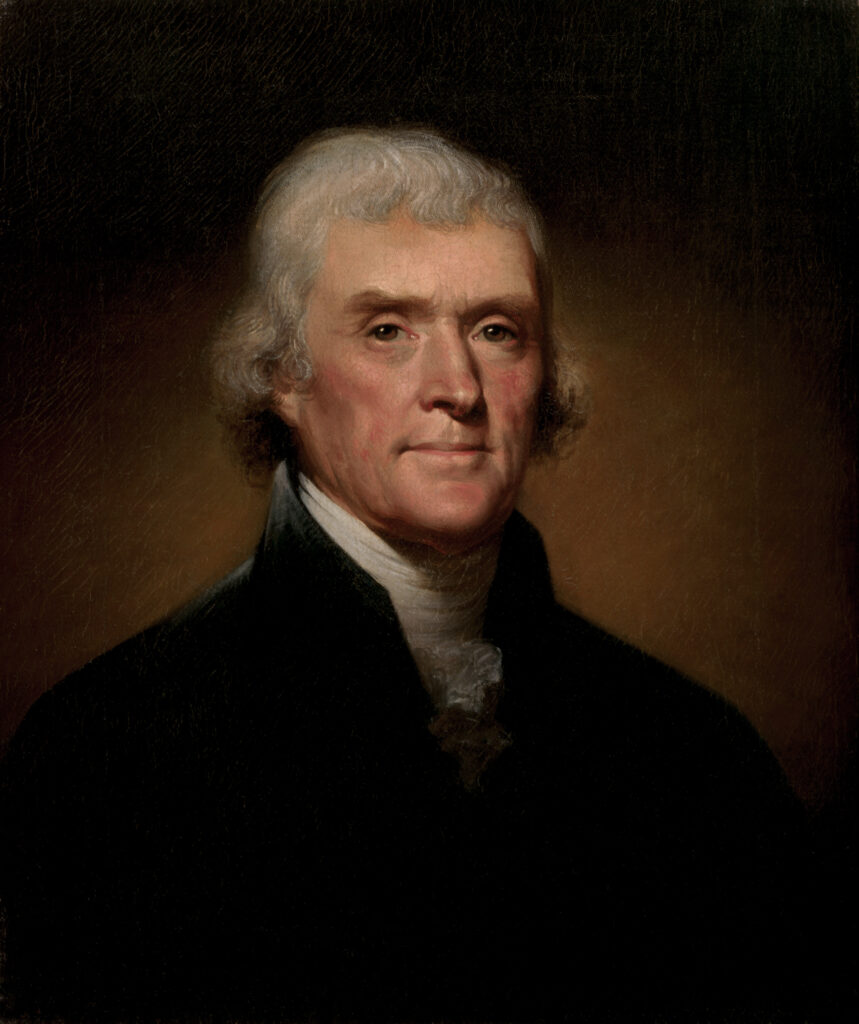

For the next 100 years, the trials and tribulations of the Academy were in many respects the trials and tribulations of progress of science in New York and other states of the new American republic. In March 1817, James Monroe became the fifth American president. That same year he was elected an honorary member of the Lyceum, along with the third American president, Thomas Jefferson.

The intentionally anti-patrician nature of the Lyceum not only distinguished it from other institutions of the day, it served as the basis for a new type of democratic institution that later was instrumental in the progress of science, especially in the New York City area, though this was also felt throughout New York State and beyond.

On the national scene, Philadelphia, originally owing to its centrality as the first American capital and birthplace of major figures in politics and science—e.g., Benjamin Franklin—was home to the first science societies in the nascent country, although with the exception of Franklin’s Academy of Natural History the societies were aristocratic and elitist. They were institutions largely, if not exclusively, for men of wealth who were not themselves scientists; nor probably even much interested in science. Membership was a symbol of status, indicating, among other things, that a person had the financial means to support these 19th century social clubs.

Even by name—Lyceum: an institution for popular education providing discussions, lectures, concerts, etc.—the first incarnation of the Academy was fundamentally different from other societies. Its raison d’être was not social climbing and show, but the dissemination of science, and bringing people who were keenly interested in science, together.

This fundamental democratic principle determined the course of the Academy’s history, and with it the development of key institutions of science and learning in New York City today, including Central Park, the American Museum of Natural History, the New York Botanical Garden and New York University. It was by inclusion of people on the basis of only their interest in science that the Academy could bring together so many different stakeholders—indeed so many key individuals at just the right moments—to influence, if not forge the development of many New York City institutions.

The founding meeting of the Academy, then the Lyceum, occurred on January 29, 1817. To tell the history of the Academy’s accomplishments since then is to tell the history of science in New York State and America, and beyond. It is the history of an institution, but more importantly of the tens of thousands of individuals who have been Academy Members since 1817, from around the globe and from many diverse institutions, cultures and walks of life.

Indeed the history of the Academy would not have been possible without the devotion, energy and creativity of its Members. This collective engagement—today we refer to this as the Academy’s network—has enabled and driven fundamental changes in the landscape of science and science-based institutions in New York City and throughout the world. This is history worth telling, and re-telling.

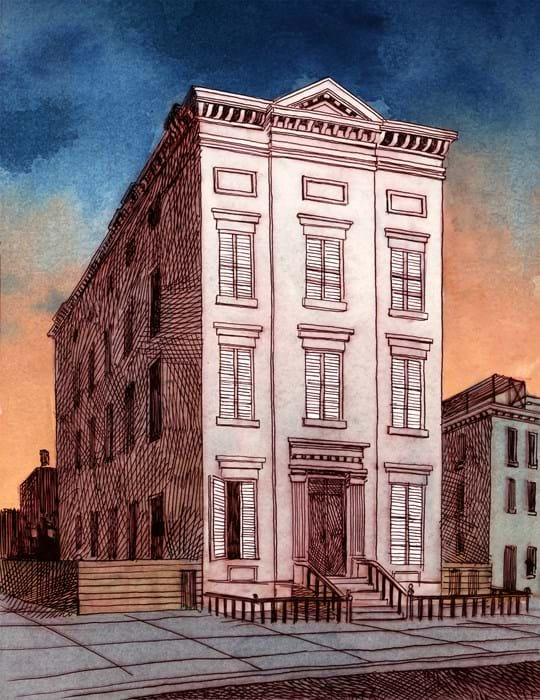

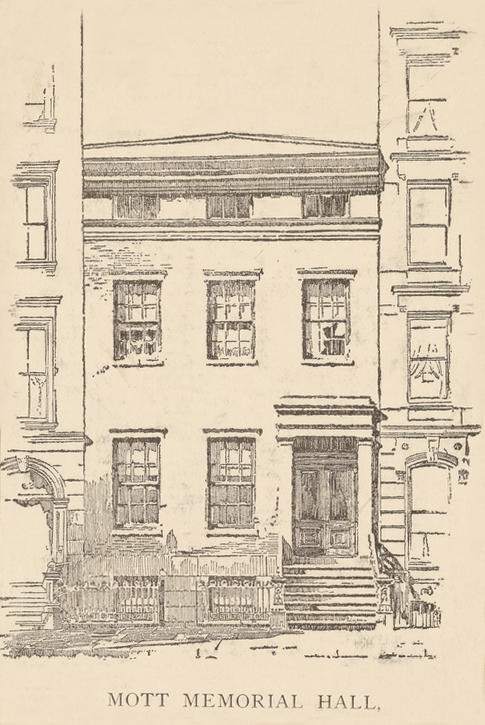

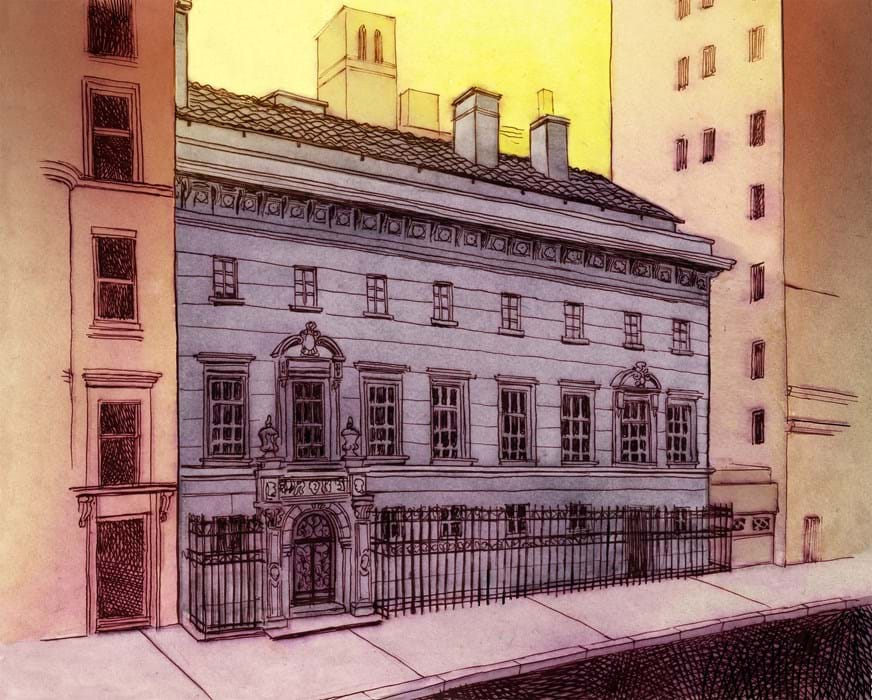

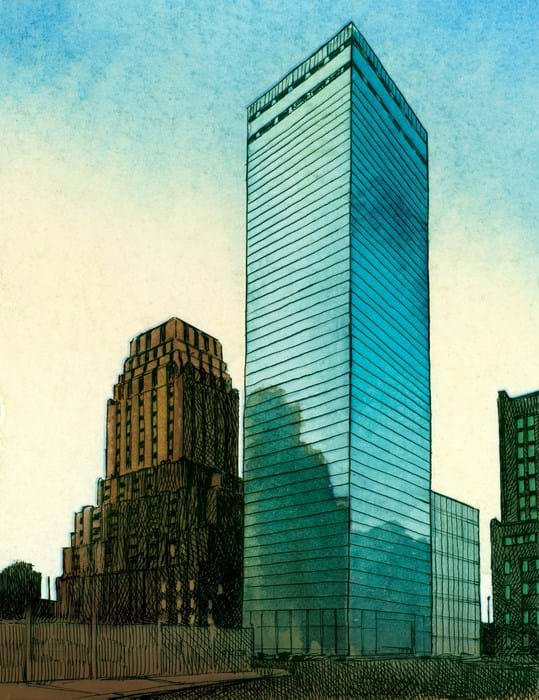

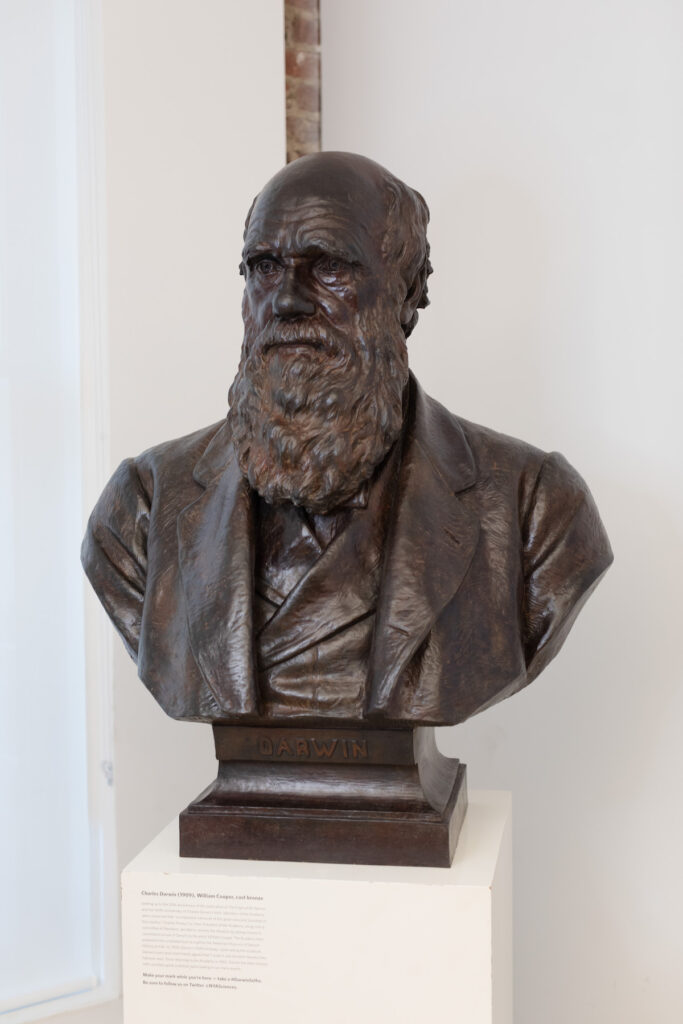

Two centuries later, on January 29 2017, the Academy unveiled a permanent 200th Anniversary Exhibition in the lobby of its headquarters at 7 World Trade Center in New York City (see photos below). The folded timeline insert in this issue of the magazine provides a concise history of key Academy events, members and accomplishments since 1817. A prominent feature of the physical exhibition is a 17-foot-long timeline with images and text that tells the story of some of the enormous challenges and successes over the Academy’s 200 years.

In addition, as part of the 200th anniversary celebration, the Academy is publishing a revised edition of a critically acclaimed history of the Academy and of science in New York City and the early United States, Knowledge, Culture, and Science in the Metropolis: The New York Academy of Sciences, 1817–2017 by historian and professor Simon Baatz (John Jay College).

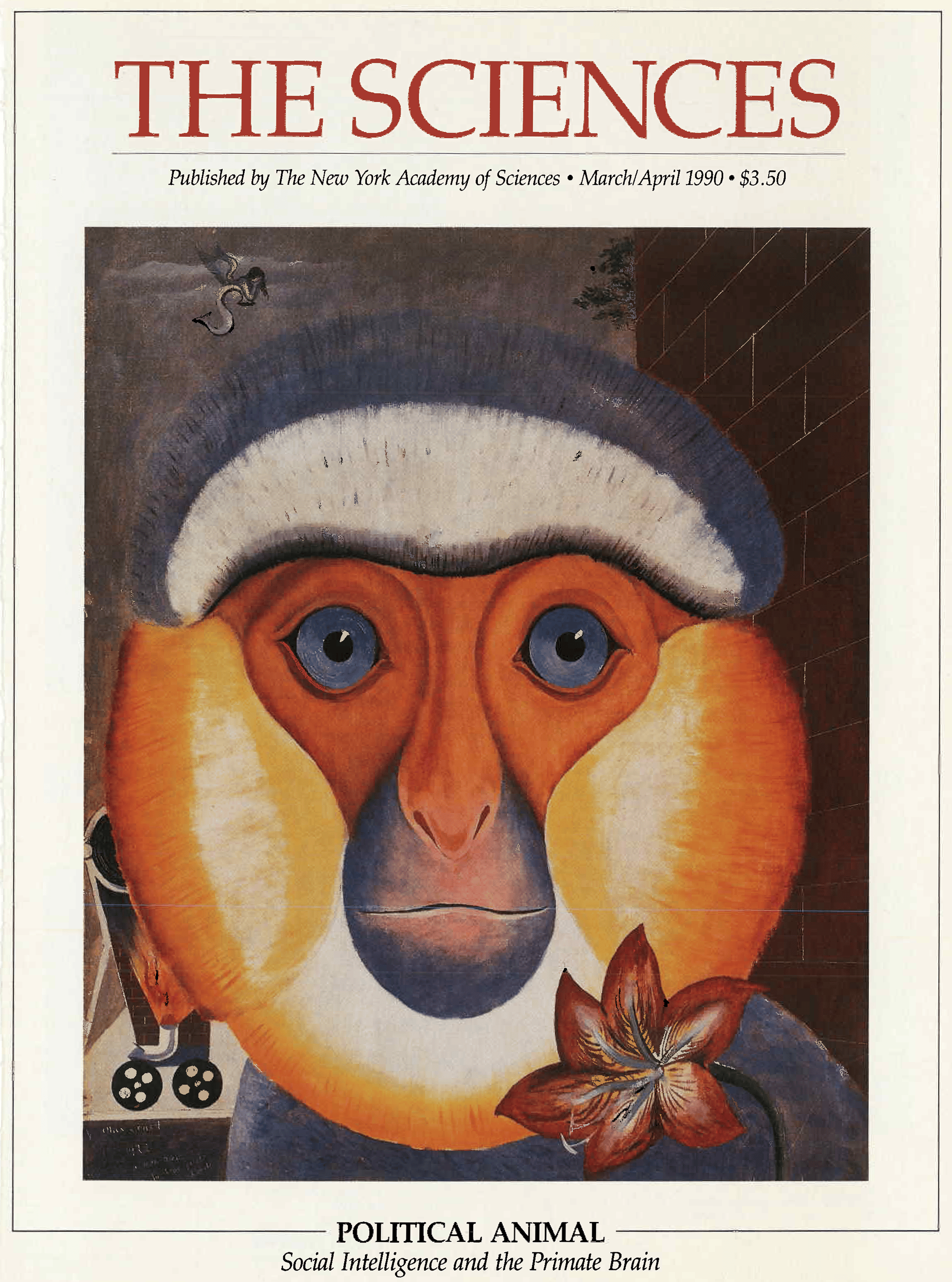

Originally published as special issue of Annals (Ann NY Acad Sci 584: 1–269) in 1990, professor Baatz’s book provides an, “engrossing account of the role of the sciences within the great American metropolis”… “this masterly account of science in its social context will be of the greatest interest to everyone who cares about New York, about the growth of knowledge, and about the importance of voluntary associations in our national life.” The revised edition, published in January 2017, contains a new chapter on the Academy’s history from 1970 to 2017.

An even earlier account, A History of the New York Academy of Sciences, formerly the Lyceum of Natural History, published in 1887 by Herman Le Roy Fairchild, is also available in electronic form by contacting the Academy at annals@nyas.org. Fairchild’s account is a detailed discussion of many facets of the Lyceum’s early days, including biographical sketches of many of the important founders, lists of all of the first Lyceum officers and administrators, dates and addresses of locations of the Academy during its early peripatetic days, copies of the original constitution, by-laws and other legal documents.

Finally, a very brief history, “The Founding of the Lyceum of Nature History,” by historian Kenneth R. Nodyne, was published in 1970 (Ann NY Acad Sci 172: 141–149).

Some Prominent Members of the Academy

From its inception, the Academy has been a member-driven organization. And while it was a democratic organization that welcomed anyone, the Academy, for its first 100 years or so, proposed and voted on bestowing memberships.

As specified in the original constitution of 1817, admittance to the Lyceum was by three categories of membership. Resident members were from NYC and “its immediate vicinity” and thus could take part in Academy meetings, while Corresponding members, largely on account of travel times in the early 19th century—it took a day and a half to travel to Boston!—were less involved; Honorary members were selected on the basis of “attainment in Natural History,” no matter where they resided.

Categories of membership changed over the years. In the 1980s there were eight: Active, Life, Student, Junior, Institutional, Certificate, Honorary Life and Fellows. The total number of members had reached its highest, 48,000 from all 50 states and over 80 countries around the world. This membership apogee was in large part the result of two factors. One was the enormous influence of the Academy’s executive director from 1935 to 1965, Eunice Miner, whose zeal and “stubbornness” increased membership from 750 in 1938 to over 25,000 by 1967! The other influence was a membership policy in the 1980s of mailing out membership certificates to people worldwide.

Today’s Academy membership of 20,000 is composed of Professional, Student and Postdoctoral, Supporting and Patron, and—continuing a long tradition—Honorary Members. Over the course of our history there have been well over 200 Honorary Members, including 110 Nobel Laureates. Below are profiles of just a few of the Honorary Members.

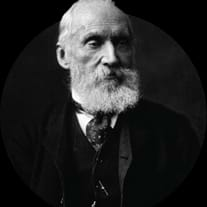

Lord Kelvin (1824–1907)

Elected Honorary Member 1876

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, a Scots-Irish mathematical physicist and engineer who did important work on electricity and thermodynamics. Absolute temperatures are stated in units of Kelvin in his honor.

Louis Pasteur (1822–1895)

Elected Honorary Member 1889

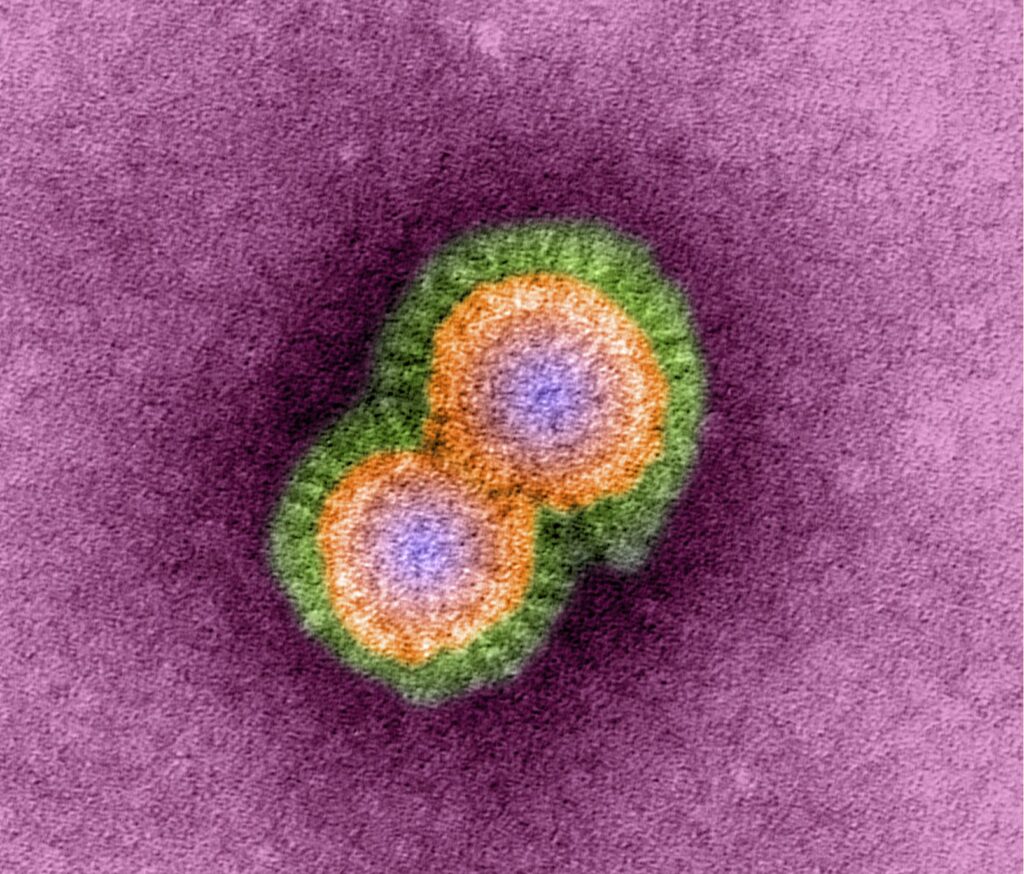

A French chemist and microbiologist known worldwide for his work on understanding vaccination, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization. He was director of the Pasteur Institute, established in 1887, until his death. He was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in 1853, promoted to Commander in 1868, to Grand Officer in 1878 and made a Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor—one of only 75 in all of France.

Niels Bohr (1885–1962)

Elected Honorary Member 1958

A Danish physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922 for making fundamental contributions to the studies of atomic structure and quantum theory. He spent much of his life and worked in Denmark, where he founded the Institute of Theoretical Physics at the University of Copenhagen.

Barbara McClintock (1902–1992)

Elected Honorary Member 1985

An American cytogeneticist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1983 for her discovery of genetic transposition. Her work concentrated on studies of maize, for which she developed techniques for visualizing the chromosomes; she produced the first genetic map for maize and demonstrated the important roles of telomeres and centromeres. McClintock spent her entire professional career in her own laboratory at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

Rosalyn S. Yalow (1921–2011)

Elected Honorary Member 2006

Born in New York City, Yalow was a medical physicist and co-winner of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the development of the radioimmunoassay (RIA), an in vitro technique used to measure concentrations of immune proteins called antigens. This revolutionary technique helped to marshal in the modern era of immunological research. Yalow also won the prestigious Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research (1976) and the National Medal of Science (1988).